Compositional reasoning and a car

When you write code, you want it to have some properties. It might be as simple as “it works”, which is the least precise the functional property :) You may also want the code to be fast, memory-efficient, and failure-tolerant. There are many properties to choose from.

Whether you are conscious about it or not, when you write code, you reason about it. You do it at least to persuade yourself that the code behaves as desired.

The problem is that all the properties you usually want to hold are global. Even the simplest “it works” talks about the program as a whole. Considering that your codebase might be hundreds of thousands of lines of code and your brain is capable of holding around 7 things simultaneously1, verifying those properties might be unbearably hard.

Even if you carry out the proof once, your code is not static, and you have to redo the whole process as soon as you change a single line. Moreover, you have to write the code line by line in the first place, being guided by something…

Compositional reasoning

Meet compositional reasoning. The thing you always do but might have never recognized. You start by decomposing the whole system into parts. You then formulate and prove the local properties of those parts. Finally, you derive the global properties by composing the local ones.

To prove the local properties of the parts, you may proceed with compositional reasoning recursively. You consider the part as a whole interpreting the local property as a global one, and repeat the process. You recurse until you end up with parts as small as a single line of code or even a single token.

I intentionally used the term “part” because it can refer to any unit of decomposition provided by your build system or language. This could be a library, a package, a compilation unit, a module, a class, a method, a control statement, an expression, or anything in-between and beyond.

A car

To demonstrate the power of compositional reasoning, we will consider an example not related to software at all!

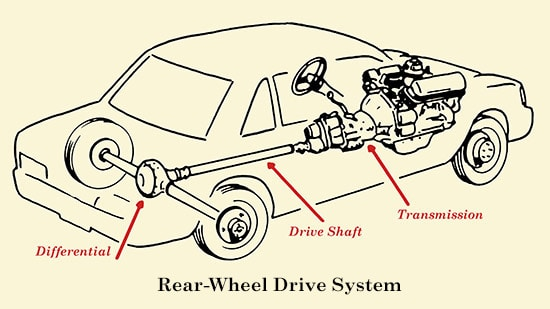

Taken from www.artofmanliness.com.

Taken from www.artofmanliness.com.

Imagine a typical rear-wheel drivetrain of a car. It consists of an engine, a transmission, a drive shaft, a differential, and rear wheels. All are connected by smaller shafts in a chain. Let’s say we want to prove that when you press the pedal, the rear wheels spin.

This is a global property that describes how the system acts as a whole, but the car consists of thousands of small parts, and thinking about how all of them interact with each other is impossible!

Fear not! Compositional reasoning to the rescue. We can simplify the task by decomposing the system into parts, formulating and proving the local properties of the parts, and proving the global property by composing the local properties.

Let’s start with the engine. When you press the pedal, the engine rotates the outgoing shaft. This shaft goes into the transmission, and the transmission in turn rotates its outgoing shaft. This shaft is connected to the drive shaft. The drive shaft preserves the rotation and passes it to the differential. The differential rotates its two shafts which are connected to the wheels.

We have just jumbled all the steps into a single chunk of text. It is time to figure out the individual pieces. Our local properties are the following:

- The pedal is pressed.

- When the pedal is pressed, the engine rotates its outgoing shaft.

- When the transmission’s ingoing shaft rotates, its outgoing shaft rotates.

- The drive shaft preserves rotation.

- When the differential’s ingoing shaft rotates, its outgoing shafts rotate.

- When the shafts connected to the rear wheels rotate, the rear wheels spin.

Having proved those properties, you can easily compose them and derive the global property we started with. You start with the pedal and apply all the other properties one by one (modus ponens).

Local properties

But what makes a property local to a part? It is not just that it talks about that part only, it is that it is provable for that part in isolation. Note that each of the properties is of the if-then form (except for the pedal). Each of them doesn’t just formulate the outcome (the conclusion). It also formulates what must be true for the outcome to hold (the assumptions, the preconditions).

Consider a property “the transmission’s outgoing shaft rotates”. This property is not local to the transmission, because to demonstrate that property you need to consider all the other parts. If you disassemble the drivetrain and put the transmission aside, its outgoing shaft won’t rotate! This property is not true for the transmission in isolation but it is true if you consider the system as a whole, which makes this property global and not local.

Looking back

You might argue that it is a lot of work for a single property, but instead of a single complex problem to solve, you now have several that are much more tractable. Each of the local properties can be established completely independently. You can even delegate the individual tasks of establishing a property to other team members. The nice part is that they don’t need to understand the whole system, only the part they are responsible for.

However, what is even nicer is that this reasoning scheme is resistant to changes. If you want to change the transmission, it is enough to verify that the new transmission has the same local property (which again can be done in isolation), and the rest will follow.

Compositional properties

Note that the properties of all the intermediate parts between the engine and the wheels are suspiciously similar. We can formulate a property that is generic over the part: “It preserves rotation”. Note that each of the local properties of the intermediate parts is a particular instance of this generic property.

This property is an example of a compositional property, a property that composes, i.e. if the property is true for each part, it is true for the composition of the parts.

Note that we can compose the local properties of the intermediate parts and derive an instance of the same generic property for the intermediate parts as a whole: all the intermediate parts preserve rotation. From this property, it is immediately clear why the rotation of the engine’s outgoing shaft results in the wheels spinning.

Back to code

Replace the car parts with software modules (or any other unit of decomposition but it is easier to talk about modules), and you can see how to apply compositional reasoning to software systems.

Local properties have many names. One of the most widespread is contract. Note that any of those properties only talks about the observable behavior of a part, not its internals. Each of those properties declares what the part promises to do providing that the obligations on other parts hold. This is why you can call such a property a contract2.

Connection to other ideas

High cohesion, low coupling

This is where this design principle stems from. It is needed to ease the compositional reasoning. You want each part to be cohesive to ease the local reasoning, and you want the parts to be loosely coupled so that more global properties remain true after a local change.

Building abstractions

Another prominent variation of compositional reasoning is the idea of building layers of abstraction.

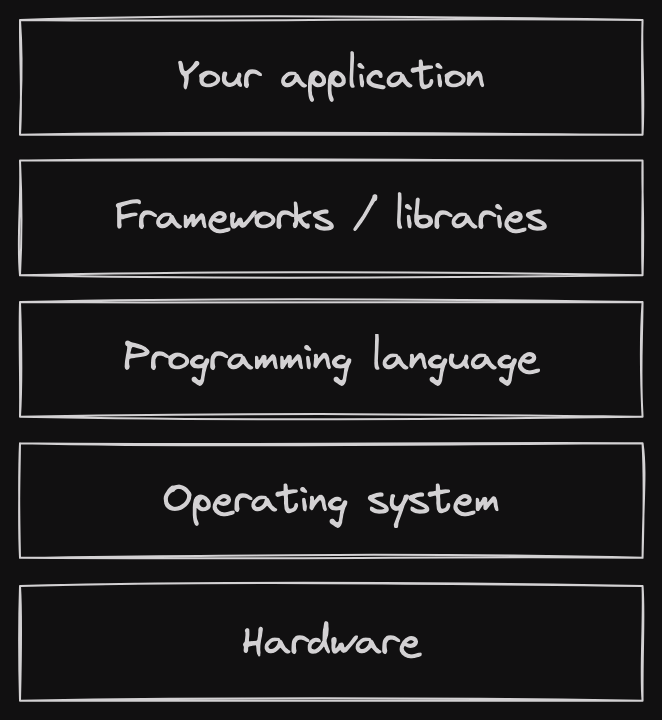

Layers of abstraction.

Layers of abstraction.

Your application is just another layer built on top of other layers such as your favorite framework, operating system, and hardware. Each layer is a unit in the compositional reasoning scheme. An abstraction is just a concept in a single layer with associated properties. Each layer delivers its abstractions and properties based on the abstractions and properties of the previous layer.

Dynamic analysis

We have been talking about reasoning about the code statically. That is, looking just at the code and its structure and never running it.

You might argue that one could have verified that pressing the pedal causes wheels to spin just by igniting the engine and testing it, and you would be completely right. Such a level of understanding is enough for a regular user but insufficient for a car mechanic.

Checking properties of code by running it is called dynamic analysis, and unit- and integration testing is one of its forms. Profilers, sanitizers, and interpreters (like Miri) are other well-known forms of dynamic analysis.

What is so great about compositional reasoning is that you don’t have to reason about everything statically. You can find out the local properties of some components dynamically, whether by using a profiler or carefully staging an experiment. You may even just believe what is written in the documentation to a component.

Of course, the weaker the evidence, the higher the chance that you are wrong. However, the moral is that you don’t have to understand each piece in the whole abstraction stack, as well as a mechanic, who doesn’t have to understand the role of each gear and cog. This is why abstractions are created in the first place.

Mocking

Remember that a local property often relies on assumptions about other parts of the system. How can you unit-test a local property? This is where mocking comes in. You substitute a mock instead of the real dependency which only exhibits the assumed properties, and test that those properties are enough for the tested property to hold.

Conclusion

There is still more to cover: why undefined behavior is so bad, what makes writing OS kernels so hard, and why minimizing unsafe in Rust makes so much sense. All of the topics are directly related to compositional reasoning. However, this post is already too long. So we will cover all the other topics in future posts.

To sum up, compositional reasoning is the basis of how we, humans, reason about complex systems. As we have seen, a lot of tools, principles, methodologies, philosophies, etc. are there to aid it. Of course, you always have been applying it but I hope that this post has made you a bit more conscious of it and has shed some light on why we do the things the way we do.

Future reading

- https://dominik-tornow.medium.com/the-magic-of-abstractions-658da757b936

- https://www.tedinski.com/2018/04/24/design-and-property-tests.html

-

Yes, I know you can’t compare such numbers directly but such a comparison is here just to give a sense of scale. ↩

-

There is an associated design methodology called design-by-contract and even programming languages built around it (e.g. Dafny). This methodology is basically a formalized and mechanized form of compositional reasoning. ↩